This past January, as thousands of protesters flocked to JFK in support of those who had been detained in the wake of President Trump’s travel ban, the New York City Taxi Workers Alliance (NYTWA) released a statement condemning the ban as “Islamophobic,” and, in solidarity with those affected by the ban, ceased picking up passengers at JFK.

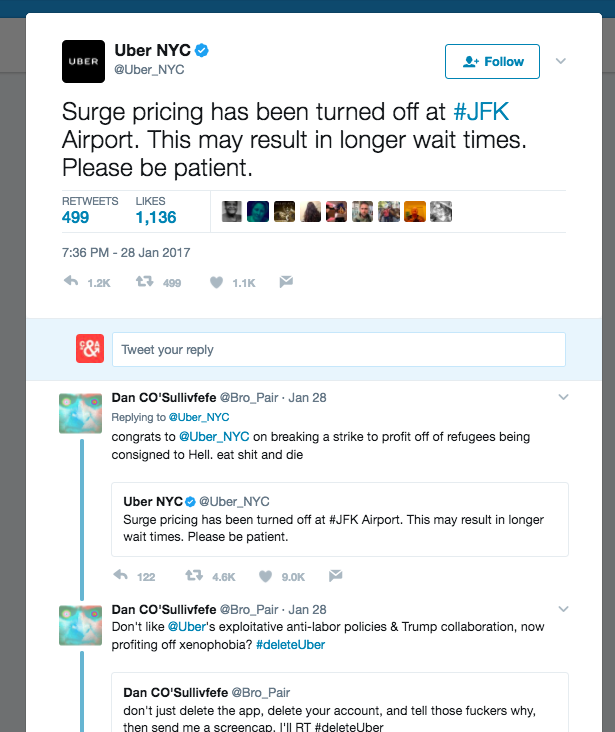

Meanwhile, Uber also released a statement via Twitter. In seeming direct response to the NYTWA statement, not only would they continue picking up passengers at JFK, but they would also lower their rates and turn off surge pricing, effectively breaking the strike. The backlash was instantaneous. The hashtag #DeleteUber began trending on Twitter, and by the end of the week more than 200,000 Uber users had deleted their accounts. And while this amounted to only a small fraction of Uber users, the implications were disproportionately grandiose.

In the coming hours and days, Uber CEO Travis Kalanick released a statement opposing the travel ban, resigned from President Trump’s advisory council, and promised to compensate drivers affected by the ban and offer them pro bono legal counsel. And while this was by no means the first time a company had been punished for a political opinion or action since the election, Uber is a giant global corporation, and the world took note.

The message: for businesses in the Trump era, politics matter.

In the months since the 2016 election, this message has resounded louder and more clearly. Nordstrom’s dropped Ivanka Trump’s line due to poor sales, Breitbart News lost 90% of its advertisers in two months, and, after people started tweeting pictures of flaming New Balance sneakers, New Balance was forced to issue an apology for a statement made regarding their views on the Trump administration’s trade policies.

Source: Newsweek

The Uber scandal, and similar post-election scenarios that followed, seemed to have awoken us to a latent knowledge of the political force behind the choices we make as consumers with our dollars. In a technological milieu of human-centered design and customer-first thinking, it appears that brands are ready to give us exactly what we want.

But to what extent? How much can we demand? And what if what we want is something that is bad for us, or what’s more— for others?

Will Silicon Valley resist Trump?

Such questions raise further questions regarding the role of Silicon Valley in our lives and in politics. Like the entertainment industry before it, Silicon valley–with the tech and the money and the data that run through the tributaries of its platforms– is now the purveyor of culture. And in this world where tech companies influence everything from what we do when we first wake up in the morning to who we vote for, what is their role in the so called resistance?

For starters, do they have a role at all? And if so, is resistance good or bad for their businesses? Should it even matter? And finally, who are these companies responsible to? Their users? Their stakeholders? Their employees? The country? Where are their allegiances?

These are some of the questions that animated a panel entitled Will Silicon Valley Resist Trump? at the Northside Innovation Festival in Brooklyn last week. The panel, moderated by The Intercept’s Ryan Tate, included tech journalist and founder of Recode, Kara Swisher; CEO and co-founder of Meetup, Scott Heiferman; tech journalist at The Intercept, Sam Biddle; and the tech blogger and entrepreneur Anil Dash.

The hour-long session provided a platform for the panelists to spar, debate, and align on such issues as labor organization, the politicization of platforms, and where Silicon Valley’s motives might lie when it comes to political resistance.

What they did agree on was that everyone in Silicon Valley is very aware of how important politics is and will continue to be to their businesses in the coming years.

Many tech companies are struggling to balance public perceptions of themselves as socially-minded saviors of the world and the interests of their employees and users with their own business interests and their reliance on the government, not only for workers, but for business friendly policies. And as it turns out, these interests are often in conflict.

Conflicting interests

In a survey conducted in December of 2016, The Intercept’s Sam Biddle asked nine tech companies a hypothetical question: would they be willing to sell their services to help the government create a national Muslim registry. Of those surveyed, only three responded, and only Twitter said no. Booz Allen Hamilton declined to comment, while Microsoft responded with a statement about “refusing to talk about hypotheticals.”

When Biddle expressed his surprise at the responses (and non responses) he received to the survey, Scott Heiferman, the only CEO of a tech company on the panel, responded with “these people are busy.” Biddle pushed back, calling the survey “low hanging fruit,” especially for companies so often eager to paint themselves as humanitarians.

And while the speculative nature of such a question may seem outlandish now, IBM set a precedent when, during World War II it devised (and profited from) custom technology that automated and optimized Hitler’s systematic extermination of the Jews, ensuring that the Holocaust’s notorious death trains “always ran on time.”

For Swisher, the question of where the interests of these companies (and the people that run them) lie, must remain top of mind. “Being rich means you have certain interests no matter how you slice it” she said. For companies who claim to put “people first,” it’s important to question, which people?

Platforms are political

It wasn’t long ago that we considered our platforms not only benign but benevolent. Travel back less than a decade to the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street, movements facilitated largely by social media, and the liberals decrying Facebook and Fake News today were singing a different tune. These movements burnished in so many a utopian optimism in the power of social media platforms to unite, to organize, and to give voice to once subversive ideas. And while our platforms still contain within them this same capacity, we have seen their limitations, and are now privy to the dark side of what happens when anyone can share ideas and information (including misinformation) with such ease and speed and of how catering to human desire inevitably reveals its depravity.

As Anil Dash proclaimed early on in the panel, “we now know that our platforms are deeply political.” Dash has been saying this for a long time, but with the rise of Fake News and the influence of Facebook on the 2016 election, this idea has finally begun to sink in, and as we have seen with Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook since the election, it is becoming increasingly difficult for tech companies to hide behind the veneer of benevolence. As Biddle pointed out, one of the most successful and dangerous uses of Twitter can be observed right now, in the President of the United States.

If it is indeed the platform–and not just the person–that is political, then resistance requires a change at the level of technology, not just culture. As Heiferman remarked, “the most powerful thing Cheryl Sandberg can do is to change the ways these platforms work.”

Taking responsibility–for the good and the bad.

In Swisher’s view, Silicon Valley is overgrown with what she calls “delicate flowers”–people who are deeply invested in the public’s perception of them as “good people,” but who are highly sensitive to any suggestion that they have anything but the public’s best interest in mind.

“What’s exhausting is when they see themselves as better people but aren’t willing to follow through when there is pain,” she explained. “This isn’t Wall Street. They want to appear to have a conscience.”

Her complaint isn’t unfounded. When things are going well, there is plenty of evidence that these companies are quick to claim credit, but when they go awry, there is a tendency to shift responsibility from the platform to the people. In 2012, for example, on the heels of the Arab Spring and Facebook’s decision to go public, Mark Zuckerberg released a statement describing how by “giving people the power to share,” Facebook was “starting to see people make their voices heard on a different scale from what has historically been possible.” He goes on to describe how Facebook hoped to ”change how people relate to their governments and social institutions.” Fast forward to 2017, when, after failing to remove dozens of images of child pornography from their site, it wasn’t, according to Zuckerberg, the platform, but human error that was to blame.

For all of the panelists, the failure of companies to own up to the gains and the ills made possible by their platforms is a major problem. As Swisher aptly stated, “with self driving cars alone, millions of jobs will be lost. Who is responsible for that?”

We’re excited to kick off our first day at InsureTech Connect listening to Credit Karma CEO Kenneth Lin talk about Auto Hub, Credit Karma’s online hub for automotive information. Launched late last year, Auto Hub allows members to manage all the information they might need about their automobile, from loans and leases to recalls and important DMV information. Lin will be taking the stage to unveil exciting news about what is next for Auto Hub.

The imperative to organize and mobilize

“Even if you are getting paid well doesn’t mean you aren’t getting f*****,” was Biddle’s fiery response to Swisher’s suggestion that for Silicon Valley workers, supposedly the best-treated employees in the world, the idea of unionizing is silly. “Well they do need fresh Kombucha. It’s a little bit stale,” she joked.

And while panelists did not agree on the question of unionization, they did generally align on their support for the kind of organization they have seen happening amongst tech workers since the election.

Unlike the majority of their employers, who refused to state whether or not they’d be willing to participate in a muslim registry, in December, a coalition of hundreds of engineers at major tech companies across Silicon Valley signed the “Never Again” pledge, refusing “ to participate in the creation of databases of identifying information for the United States government to target individuals based on race, religion, or national origin,” while also promising to advocate within, raise awareness, and hold their organizations accountable. For Anil Dash, this kind of organization of workers within tech companies is where the real resistance is at. “Suddenly seeing that level of organization among the people doing the work was inspiring,” he said.

Furthermore, Dash believes this kind of organizing can open the door for others involved in the tech world who aren’t getting rich—the bus drivers, cafeteria workers, and janitors—those, in other words, who may be worried about more than stale Kombucha.

Heiferman, who frankly stated, “I can’t believe my employees don’t unionize,” believes that whether or not employees decide to unionize, it’s in the best interest of companies and their employees to respond to political crisis alongside their employees.

“When my employees, in the hours after the travel ban kept asking what are we doing, you know that the Facebookers and Googlers are doing the same” he said.

Heiferman has a history of mobilizing his business to respond to political crisis. Meetup was founded in the shadow of 9/11 with the express purpose of contributing to the greater good of society by facilitating person to person connections, something which he understood the true value of only after living through 9/11 in Manhattan.

In response to his employees’ desire to do something after President Trump signed his travel ban, Meetup paused operations, and in partnership with a number of civil rights organizations, created 1,000 Meetup groups under the hashtag #Resist. And while the move had the effect of alienating Trump supporters from using the platform, Heiferman felt it was his civic duty to resist the new administration’s policies around immigration by “mobilizing people.” It was also a means of engaging his employees in political activism, something which all the panelists agreed was, aside from addressing the platforms themselves, one of the most potent forms of resistance against the current administration.

So, will Silicon Valley resist Trump?

It depends on who you ask.

Those on the other side of the fence would say they already have, Breitbart News accusing Silicon Valley of being “the center for the Anti-Trump resistance”. Meanwhile, Peter Thiel, vocal Trump supporter and Silicon Valley’s most reviled billionaire, has pointed the finger at Silicon Valley for what he believes to be their self-interested resistance to Trump, based less upon any grand ethical commitments they may have than on how the administration’s trade policies and stance on immigration will affect their business interests.

While the panelists certainly do not share Thiel’s enthusiasm for Trump, their opinions were hardly less cynical; there was little indication that any of the panelists were optimistic that Silicon Valley would resist Trump in any way that conflicted with their own business interests. Without pressure from the masses, it seems unlikely that they’ll go beyond this.

Until Silicon Valley begins to take seriously the influence their platforms have on society–for good and bad–it is up to individuals–employees, users, consumers, and activists–to organize and mobilize to hold Silicon Valley, and the rest of the corporate world accountable to their best interests and those of society at large.

For large businesses, especially those in tech, the pressure to take a political side is only increasing. As our nation becomes more polarized politically and economically, and as business interests continue to collide and conflict with those of employees, users, and society as a whole, it remains to be seen how businesses will navigate the touchy terrain of politics without tripping calamitously along the way. In the words of Virginia Woolf, “the future is dark, which is the best thing the future can be, I think.”