The internet is “the world’s best fact checker and the world’s best bias confirmer, often at the same time” – Michael Lynch

On Sunday afternoon, as people across the country were receiving news alerts about a shooting in Sutherland Springs, Texas, information began to circulate about the shooter. A member of Antifa. A Christian-hating communist with a revolutionary agenda. An atheist on the DNC payroll. A man named Sam Hyde. Or so the story went.

While the shooting that took place was tragically real–as tragic and as real as Sandy Hook, and other events that certain media outlets and personalities have recently attempted to discredit–none of the information circulating about the shooter, or at least not that we know of now, has proven to be the slightest bit credible.

These false stories have comprised the latest incident in what has become something of a national crisis – a crisis of communication, of credibility, a crisis of facts– as seen in the phenomena of Fake News.

Defining the Problem

It’s hard to believe that only a year ago Fake News as a phenomena and a societal concern was hardly on our radar. Since the 2016 election the term has become something beyond commonplace: a frequent refrain of presidential Tweets, partisan shorthand for both fake and legitimate news sources, the theme of any number of think pieces, and even the subject of FBI inquiry.

And while we may not be able to agree upon what constitutes Fake News, we do all seem to agree upon one thing: it’s definitely a problem. So what is behind our Fake News problem? Well, it depends on who you ask.

According to some legal experts, Fake News is an antitrust problem. Our tech companies –the Googles and the Facebooks of the world– have gotten too big. These companies largely control the flow of information in this country, and if purveyors of Fake News can learn how to manipulate their algorithms, they can have an inordinate amount of influence, reaching millions of people with false stories long before being detected, corrected, or stopped–as was the case with the misinformation spread about the Vegas shooter. Treating these companies as monopolies, and imposing antitrust legislation, it is thought, might encourage more competition in the space, making it more difficult and laborious for Fake News to proliferate, and reach so many people, so quickly.

Others believe Fake News to be a fact-checking problem. Fact-checking as a form of journalism (in the vain of PoltiFact and FactCheck.org) has increased by 300% since 2008 with about 65% of journalists believing the practice to be somewhat to very effective at improving the quality of political discourse. Yet despite its popularity amongst journalists, fact-checking is often perceived as partisan, with republicans less likely to consider fact-checking effective and with the fact-checkers themselves facing partisan criticism. Moreover, facts are not always what are at stake when a person decides to share a piece of content. People share stories for any number of reasons–to entertain and amuse, to start conversations, indulge conspiracy theories or to reinforce their own suspicions and biases. In a world where facts don’t matter, increasingly it seems, neither does fact-checking.

Still others consider Fake News to be an education public problem. A recent Stanford study found students of all ages–from middle school all the way through college–woefully inept at distinguishing real information from false on the internet. It’s a skill the Stanford study calls “civic online reasoning,” and one the study found to be severely lacking amongst digital natives of all education levels. Based on their research, the Stanford History Education group developed a curriculum to help educators do a better job of teaching students the skill of civic online reasoning.

Finally, a growing consensus consider Fake News to be largely, if not solely a Facebook problem. After the election, it became glaringly apparent the extent to which Facebook, as a publishing and advertising platform, enabled the dissemination of Fake News during the election. A BuzzFeed news analysis following the election found that, in the three months leading up to the election, Fake News stories earned more engagement on Facebook than the top news outlets like the New York Times and Washington Post combined. Just last week, we learned that, according to Facebook Inc., content from Russian operatives on Facebook may have reached 126 million people, many times the number originally thought. And with 62% of adults getting their news from social media, two thirds of this number from Facebook alone, Facebook has its work cut out for them if they are going to adequately address the issue.

Fake News isn’t one of these problems, it is all of them–and more. And to solve the problem of Fake News will take cooperation and vested efforts from the government, from our tech platforms, and from educators.

It will also require something of ourselves. As a UX designer, I’m interested in what I, and others in my field, can do to combat fake news using the tools of our trade, and to think through the question: is Fake News a UX problem?

In short, the answer is yes. Long before there were computers or platforms like Facebook, design has been in the business of helping users interpret information and make informed judgments. Journalism, for example, has always relied on various modes of design to help enforce journalistic standards and give readers the tools and information they need to do things like distinguish between advertisements and news articles, understand how an article is sourced, and access information of varying viewpoints. When it comes to journalism, UX is not simply about making something readable, but about helping readers make sound judgements.

In recent decades it has become increasingly difficult for UX design to play this role effectively. To fully understand why, we need to talk about cognitive biases.

Cognitive Bias Unchained

Wikipedia defines cognitive biases as “tendencies to think in certain ways that can lead to systematic deviations from a standard of rationality or good judgment.” More colloquially, we can understand cognitive biases as coping mechanisms to help us navigate a universe jam packed with information. These observed patterns of thought are the filters that aid in unconscious decision making–telling us to pay attention to this and not to that. When we are faced with “cognitive problems” such as information overload, a lack of information or meaning, or an imperative to make lightning quick decisions, our cognitive biases kick into overdrive, and take over, sometimes leading us to misinterpret information or make faulty judgements.

The effect of prioritizing certain kinds of information over others and can lead us to unconsciously do things, like construct stories and patterns out of very little information, filter out details that don’t affirm views we already possess, discard specifics in favor of generalities, favor simple explanations over complex ones, and be drawn to the bizarre rather than the ordinary (among many other behaviors).

In the age of infinite information we live in today, it makes sense that we would be more susceptible to these cognitive biases. And in fact, there are a number of new-ish technological capabilities that are exacerbating the issue.

Of course there is the internet at large, which has democratized content production and publishing to an unprecedented degree, giving anyone who has access the ability to publish content. As a result, there is simply more content available to us, which leads to an information overload that can activate our cognitive biases, and put us at risk of making faulty judgements.

But our brains don’t only have to worry about the quantity of available content, but also the quality. The rise of WYSIWYG platforms like WordPress and Squarespace have made it easier than ever for anyone to build a website and make it look like a real news site, making some of the shortcuts we have relied on in the past to quickly assess the quality of information less reliable.

From a design perspective, a site like dcgazette.com, for example, which, during the 2016 election, published a fake story with the headline “Another Person Investigating The Clintons Turns Up Dead” doesn’t look any less credible than a real news site like newyorktimes.com (although some might disagree with this later categorization).

And not only are we flooded with a constant stream of stories and articles and tweets and opinions, but we are also encouraged to act on this content rapidly–to share, to like, to comment, to engage. And with cognitive biases at the wheel, this becomes especially dangerous. Social media platforms have made it possible for content, regardless of its quality or legitimacy, to be shared widely and quickly, Facebook’s self-stated goal being to “give every person a voice,” all the while making it harder and harder to accurately assess and distinguish between these voices.

Meanwhile the data analytic capabilities embedded within these platforms give advertisers the ability to A/B test and engage in highly effective targeting. Because our cognitive biases encourage us to favor messages we are already familiar with, we are increasingly at risk of existing in siloed information bubbles in which we are only fed the information we want to hear, never having to experience the inconvenience of being confronted or challenged, even by the truth.

All of this has been accompanied by a general blurring of the lines between opinion pieces, marketing content, and journalism. One publisher’s legitimate news site looks like another person’s political blog looks like a company’s content marketing blog and so on. It is no wonder then that, as the Stanford researchers observed, digital natives struggle with civic online reasoning. The distinctions they are being asked to make have become intentionally obscured, and often invisible.

Confronting Cognitive Bias. Combating Fake News

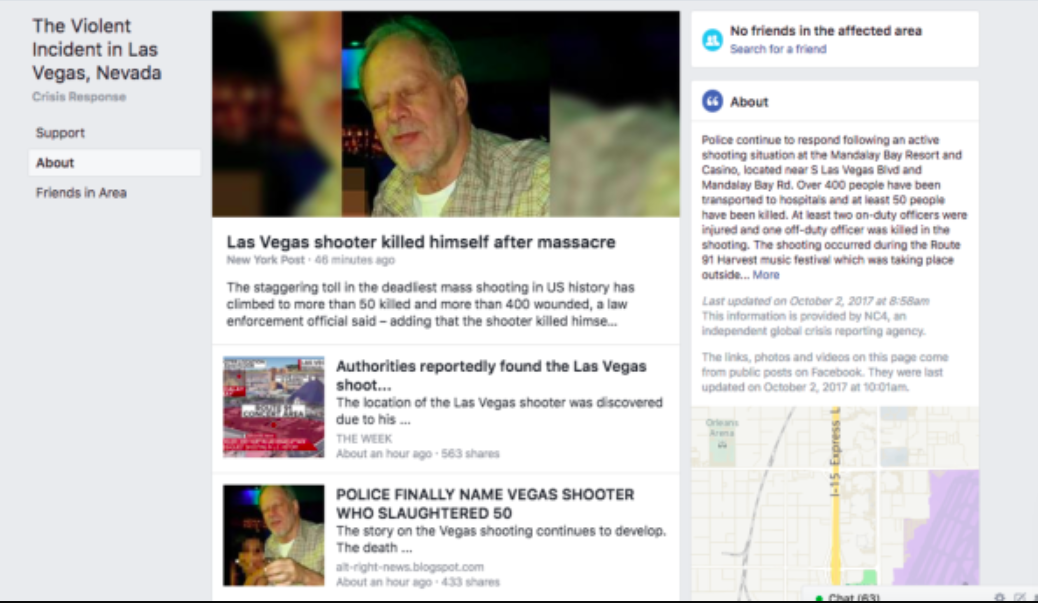

After the Vegas shooting last month, a screenshot was shared widely, showing how Facebook’s “safety check” page for the incident featured several links to articles about the shooter, including one link to the New York Times coverage and another to an article on the website alt-right-news.blogspot.com that was full of speculation, misinformation and unverified details. Both articles were more or less given equal weight by the platform, despite their vast differences in credibility. As a result, millions were misinformed about the shooter.

How did this happen? And why does it continue to happen, as we saw with the Texas shooting this past weekend? It’s a result of the forces described above combining with historical, political, and economic realities that have been at play for decades. And while admittedly this problem is a symptom of much deeper issues that go far beyond UX, as UX designers it’s possible to use our understanding of human behaviour and cognitive bias to combat some of the more nefarious problems plaguing the news industry today.

Below are three ways UX designers can confront specific cognitive biases to combat fake news:

1. Call bullsh*t

Confirmation bias is “the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms one’s preexisting beliefs or hypotheses.” Similarly, attentional bias involves the tendency to pay attention to certain kinds of information, specifically that which relates to things a person has been recently thinking about, while ignoring other information. UX designers can help brands design experiences that specifically thwart these biases by making users more aware of their own biases and giving them opportunities to be exposed to information that challenges their biases.

Over the past year, new technology has emerged that helps consumers do just this.

A number of browser extensions, such as B.S Detector and Fake News Alert are making it easier for user’s to identify the quality of a news article. Using crowdsourced data, both extensions provide visual warnings to readers indicating whether a site is Fake News or contains dubious content or sourcing. This corresponds with UX designer Joe Salowitz’s Fake Content Prevention Framework, which says that while UX should never be in the business of censoring content, it should develop mechanisms to alert users when something is fake, and help them evaluate a piece of content’s credibility.

Read Across the Aisle, an app designed by BeeLine Reader, uses visual cues in another way. Rather than alerting users to fake content, visual cues are used to indicate a news source’s level of bias. BeeLine reader is an app that is all about using UX design to influence how we consume information online. Using color theory, they have designed an app that applies gradient coloring to text, making it much easier to read online. The Read Across the Aisle app, which was launched earlier this year, is a newsreader that also uses color to influence how people read. They developed an algorithm that codes different news sources various shades of red and blue. The bluer a news source is, the more likely it is to lean toward a conservative bias, the redder it is, a liberal bias. Users can then choose news sources based upon color, and, using the same color scheme, the app will track bias in their own reading habits based upon what they read.

2. Blow open the echo chamber

Ingroup bias favoritism is the tendency to favor members of your “ingroup”–the group with whom you psychologically identify, ie. fellow members of your political party, religion, community, family, socio economic group etc. This bias can lead us to do things like evaluate members of our ingroups more positively and trust information shared by a member of our ingroup more than that of another person, regardless of its credibility or accuracy. For many of us, our social media networks have become these ingroups, in which we are connected with a group of people with whom we share similar opinions and beliefs, and excluding others. Not only does this prime us to favor the opinions of those in our social networks, but it also prevents us from even being exposed to the ideas and opinions of those who sit outside of it – creating the perfect conditions for an echo chamber.

This bias works hand-in-hand in what is known as the the illusory truth effect – “the tendency to believe information to be correct after repeated exposure.” Because we tend to be connected with mainly like-minded people on our social networks, and are continuously exposed to the same information and ideas over and over again, we become more likely to believe these ideas over others that we are not as frequently exposed to.

One way to solve this: invite your outgroup in. UX designers can work with content and publishing platforms to design ways to expose people to people outside of their “ingroup” and to ideas that challenge the opinions of the group.

One of our clients, KIND Snacks launched their Pop Your Bubble campaign this past April. As a part of the campaign, the KIND Foundation, the nonprofit arm of KIND Snacks, designed a Facebook app to help users expose themselves to other viewpoints. The app analyzes information provided by your Facebook profile to identify other Facebook users who are likely to share different viewpoints from you. The app then gives you the opportunity to “friend” these people on Facebook in an effort combat your biases and develop empathy with other viewpoints.

A similar app called Escape Your Bubble allows users to identify a group of people they want to understand more, and then the app will curate content on Facebook to appear in their feed, providing them insight and knowledge into this group.

3. Combat clickbait

The negativity bias says that our brains are wired to pay more attention to and overly emphasize negative information and experiences. Similarly, the Von Restorf effect says that our brains are attuned to seeking new stimuli, and are more likely to remember information that stands out from the rest. These biases can help to explain how clickbait works. By taking advantage of these kinds of biases, purveyors of fake news are able to garner more engagement with their content, which then becomes more likely to spread.

A recent analysis of over 70,000 articles found that people were more likely to engage with content that was on either end of the extreme- positive or negative. Another analysis found that Fake News headlines were more likely to be negative. But if people are more likely to engage with extreme headlines, and if engagement equals money, how can we prevent all news sources, fake and otherwise, from using negative or exaggerated headlines in this manner?

The answer may lie with Gmail. In 2013 Gmail launched its tabs feature, which, using an algorithm, filtered out social and promotional emails from a user’s primary emails via separate tabs. This is a perfect example of how UX can be used to organize information, and distinguish credible content from spam and advertising, without censorship.

Social and content platforms can build similar mechanisms into their algorithms to weed out Fake News in the same way email does spam or promotions, and use logical interfaces to prioritize more genuine news headlines from the clickbait.

Facebook recently embarked upon just such a solution to the problem of clickbait. In August of last year, they announced that they had begun analyzing clickbait articles to identify the phrases that often appear in their headlines. Using this information, they updated their algorithm to make stories that rely on clickbait appear lower in a user’s newsfeed. And while this was a step in the right direction, Fake News headlines are still dominating newsfeeds, suggesting the solution has not gone far enough.

By working hand in hand with UX designers to expand this logic beyond Facebook’s narrow definition of clickbait to anything that falls under the category of Fake News, Facebook and platforms like it might ultimately be able to empower users do a better job on their own of evaluating content without their biases getting in the way.

–

I’ve asked elsewhere whether it was time we, as UX designers, take a hippocratic oath of our own. Perhaps if we did, we could lead the charge in helping social media platforms like Facebook and others responsible for the spread of misinformation be more accountable, not just to individuals, but to society as a whole.