The assignment: Redesign and enhance the customer journey for a specific line of products for a fortune 500 DTC retailer. The team consisted of four Cake & Arrow vets, each from different backgrounds with varied skill sets and personalities. Everything was in place to ensure success—a thorough download of the project, access to all of the necessary resources, and alignment on what defines success.

There we were, kicking off a new engagement, something we’ve done many 100’s of times over the past 15 years. And just like that we were off and running.

Fast forward three weeks and I’m clicking through a series of working prototypes. I’ve clicked through a prototype or two in my day, but this one was different. It made me proud. It wasn’t so much any specific aspect of the prototype itself as it was what led up to and informed it–the process that brought it into being.

The past 3 weeks had been an intense, adventurous, and well-orchestrated journey toward achieving alignment, establishing momentum, and ensuring success. What started as a problem to be solved quickly turned into a well-thought out solution brimming with insights and value. This time, it wasn’t about the deliverables or artifacts, it was about the collective value that a multitude of activities (and people) ultimately delivered.

Through user research and contextual inquiry we established empathy towards the people we were trying to reach. Through co-creation and cross-functional collaboration all parties share a common understanding of the business goals and the problems we’re going to solve. Through rapid prototyping and user testing we validated assumptions and fine-tuned big ideas into actual working solutions. There is great energy and momentum. Sounds like a productive few weeks right? Indeed it was.

Looking back, it’s amazing how much our Design approach has evolved over the years to get to this point. We’re more iterative, efficient, collaborative, and focused. At end of day, this new way of making allows us to create more value in less time. And of all the pieces of our process, no part has undergone more drastic change–and is more critical to the overall success of a project–than the choices we make in the initial stages of our design projects—a phase commonly referred to as “Discovery”.

Indeed we’ve come far. But to truly understand how far we’ve come, you need to see where the journey began some 15 years ago.

The Call to Adventure

Ah youth. 2002 and the years that followed were defined by undying passion, personal sacrifice, fast driving, late nights, and an even a dose of pride and fear. The fear was rooted in my need to gain approval. And I’m not talking about approval of deliverables. I needed clients to feel like they were getting value on their investment in me. It was personal. And nothing was going to get in way of that. Not time, not scope, not bloat. My eagerness to immediately impress meant I’d naturally fall back on what I knew I could deliver—great design. And that’s exactly what we did. Omnigraffle was fired up immediately upon project kickoff. And at its expense came everything that was supposed to happen prior to that. No strategy. No specs. Discovery wasn’t even a thing yet. A competitive review was about as heavy as it would get back then. While there was a willingness to try new things, strategy decks were not an option. In fact, quite the opposite, and by design.

Prior to C&A, I had spent six years in agency candy land. It was filled with behemoth strategy presentations. Loads of business and marketing strategy were complete with situation analysis, consumer demographic segmentation, and integrated marketing plans. By gosh, even stats were presented as strategy. Billable hours were king. And that king feasted on some super-sized presentations. They were custom bound and hand-delivered. But as far as early digital design was concerned, the value was comparable to a bag of rocks.

Josh and Alex, year 1

With our newly found independence, we didn’t just simplify, we killed this phase entirely. We dove right into designing and we never turned back. Literally. Problem was we didn’t look forward either. Our projects had no end in sight. Launch dates were shots in the dark. Neither us nor the clients took them seriously. Scope was more or less “Deliver an ecommerce site”–and this was years before the emergence of ecommerce platforms like Magento or Shopify, which meant we were always starting from scratch. No out-of-the-box features, no plug-ins.

We had no vision, no scope, and no worries. We did have hair growing in some new places but that’s not important right now. Ah to be young and naive!

Caught driving the parent’s car

Going out on our own meant we had to make our own bed. Now It was time to lie in it. At first we were thrilled to be doing what we loved, on our own terms, but we quickly learned that “our terms” were in fact everyone’s but ours. Exhausted and stressed out, undervaluing ourselves and over-delivering for our clients, launch dates became as elusive as our quickly fading youth as projects got bigger and bigger. The lack of any up front Discovery planning or alignment resulted in drawn-out design phases and endless builds; without a scope or any semblance of a plan, complex customizations were resulting in too many late nights and caffeine hangovers. Needless to say, our “whatever it takes” approach began to take its toll.

Now I realize that we were basically setting ourselves up to fail and inadvertently putting our destiny at the mercy of our clients. Looking back, I realize how lucky we were to have such unusual relationships with our clients. They were like old friends from elementary school who knew you all of your innocence and purity, long before you started to care about what others think. Like us, they were young businesses who had skin in the game and a willingness to do whatever it takes to succeed. We grew up together and developed a true partnership where they depended on our expertise as much as we did on their business. And like old friends moving on to next phases in their lives, we began to worry our relationships wouldn’t scale over time.

It wasn’t healthy. It wasn’t scalable. Something clearly had to give. Thankfully, it did.

The Abyss

Demand for our services and project budgets were steadily rising. Our offering and staff had to grow along with it. The digital design industry was seeing a new breed of project managers, business analysts,and technical architects from software development companies who brought the much needed attention to detail—perhaps just too much of it. Because just like that, we went from one extreme to another–from ‘starting from nothing’ to ‘not starting until we had everything–and we began to look a lot like the agencies we had left behind. Except this time, replacing the hefty strategy decks were even heftier requirements documentation.

Like a teenage driver who just dodged a collision with a white-tailed deer, we overcorrected, becoming overly cautious where we had once been carefree and rigid where we had once been too flexible. Rather than diving into a project headfirst, we spent months dipping our toes in the water, tarrying in a long and laborious process of Discovery before we even uttered the words Design. This wasn’t unique to us. The whole industry–clients and agencies alike–was going through this.

Our “whatever it takes attitude” had taken a 360, and instead the approach was more along the lines of CYA (covering yo ass). And just like that the Wild West turned into a lock-down. Discovery was all about being on the defensive, with rules and regulations intended on protecting everyone, at all costs. “If we don’t do all of these deliverables up front then we’ll be right back to where we were last year.” And so we would spend as much as 3 months in Discovery phase, afraid of wasting our time and resources, as well as those of our clients, while in the process doing both. Don’t get me wrong, the work was phenomenal. But the journey there was far from it.

Instead of asking what the experience should do, we stated what the system will do. Rather than understanding who we were designing for, we strived to master every intricate detail of their lives. And then there were specs–tons of them–in the form of functional requirement documents, feature analysis, system requirement specs… (I literally just puked a tiny bit in my mouth writing that). We spent so much time trying to mitigate risk, that we lost focus on what we were actually there to do–Design. And for me and plenty of other craftspeople like me, that flat-out sucked. Same with understanding the audience. Doing research-based personas required 3+ weeks of recruiting, conducting, and analyzing before we even started mapping them out. Add in gorgeous poster-sized deliverables like mental models and concept maps and effort required to deliver was adding up.

It was one of the more frustrating times of my career. As a leader of young, user-centric design organization, I’d feel guilt about bypassing any user-centric activities–it went against who we were and what we believed in. At same time something wasn’t sitting right with me about how we were spending our client’s budgets. We had trouble finding that middle ground. What was the right amount of Discovery? What defined success?

What we didn’t realize at the time was that the biggest victims coming out of this were neither us nor our clients. They were the actual end-users––the customers or employees we were designing for to begin with. They ultimately got cheated out of good design and delightful experiences.

As a result, a revolution was a brewing and shit was about to get fun.

The Return

Fast forward to today: things have changed drastically, and all for the better as far as I’m concerned. What we call Discovery today has little semblance to what it looked like a several years ago. As a company, we’ve been able to gradually apply years of life-lessons and, similar to select firms like us, we’ve figured out our place in the world. When everyone, including clients, are working towards a common goal, beautiful things happen. We had shifted the focus from being in service of clients to establishing authentic partnerships with meaningful, productive relationships.

It’s easy to prioritize. It’s more fun to design. Now, we make sure that people are at the heart of everything we do–literally. We make sure that every single activity or artifact contributes to the greater goal, and that in the end, we design a product that provides value to the people who use it. It’s no longer about phases. By focusing on outcomes, teams do only what matters while cutting away the greasy fat.

Our new approach is centered around problem solving. It’s less about doing all of the things right, but instead about doing the right things to begin with. This has required a complete shift in our thinking about what the purpose of Discovery is. Where we once considered Discovery to be our preparation for a project, now Discovery is the phase in which we validate. This means we start designing and testing first, and at the end of 2-3 weeks (as opposed to 3 months), rather than decks we have prototypes and actual designs. The hard lines that once divided the Discovery and Design have become blurry, almost to the point where they are barely recognizable.

And Discovery isn’t just shorter, it’s leaner in other ways too. New user testing tools like TryMyUI and Respondent.io allow us to test sooner and more frequently. And it’s not just that we are trying to be faster or make things easier, it’s just inherent with the approach.

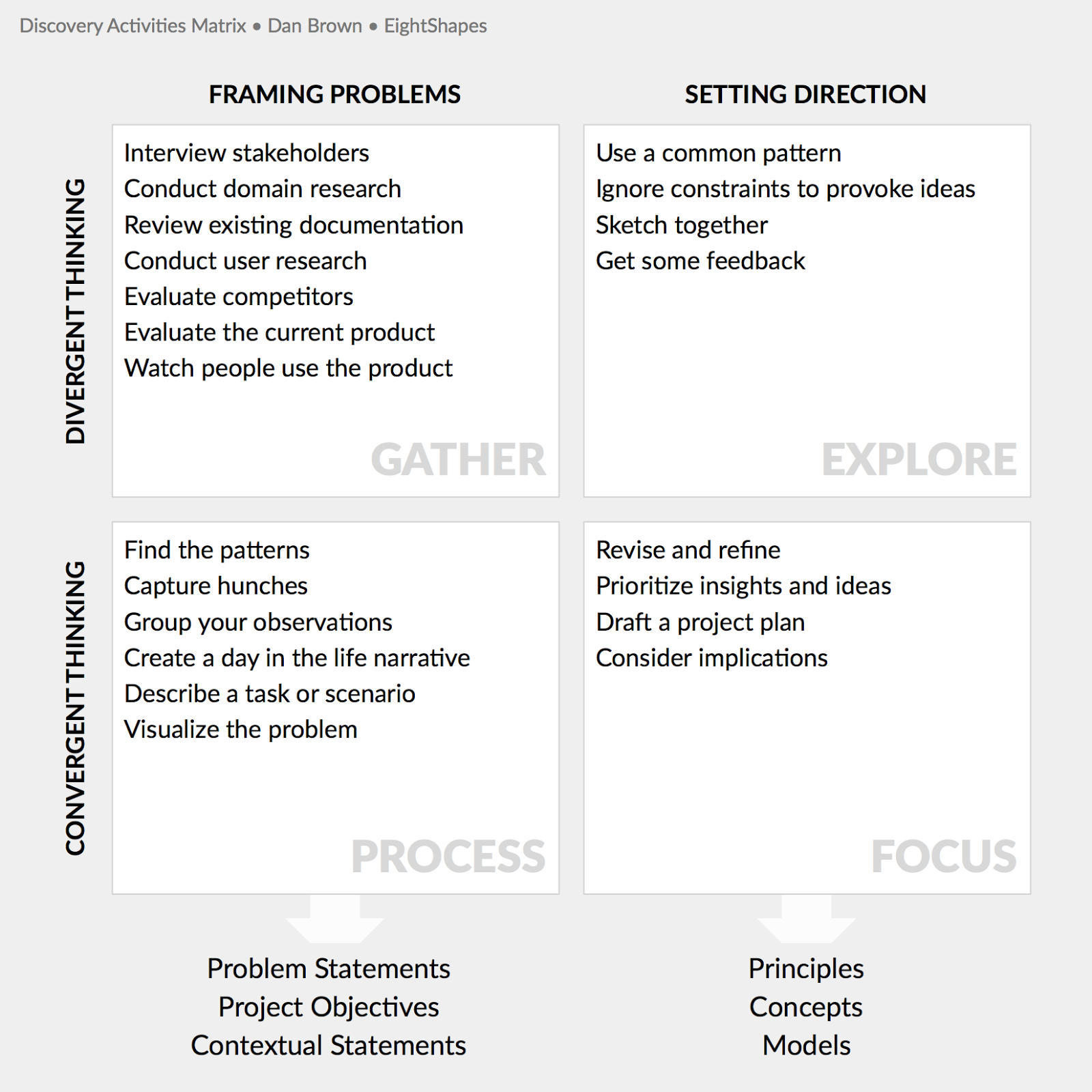

Dan Brown’s A Book Apart: Practical Design Discovery provides an excellent model for what a lean, rapid Discovery process can look like.

Dan Brown’s Discovery Matrix

Things are definitely simpler these days. And by simple I don’t mean insubstantial. The word that comes to mind is potent. Every activity we do serves a specific purpose and collectively, contributes to the ultimate goal of designing something people love. But to maintain this delicate balance between too much structure and not enough of it takes attention, tweaking, and constant reminders that people must be the heart and center of everything we do.

Discovering Value in Discovery

Ok enough with the stories. As we have come of age as an agency, we have learned a lot throughout the years about what Discovery is and what it is not, and we continue to discover more. What we are sure of, is that Discovery should always provide value. Here are a few of the key ways we’ve been able to discover value in Discovery.

1. Establish a common terminology

Try asking anyone who’s been doing this for a while what they think Discovery is and you’ll be amazed at the wide assortment of replies you’ll hear. Heaven, hell and everything in-between.

Some may share war stories like I did. There are folks who associate “Discovery” with no value and bloat. You know these folks. You’ve likely heard them say things like, “We’ve already done our own Discovery”, “Why should we pay someone to ramp up?”, “My boss doesn’t believe in Discovery. Lets just cut it out of budget.” These people are wary of Discovery for the same reasons I was:They’ve been burned in the past and, as a result, haven’t always seen the value.

Optics should be a non-factor when communicating how we approach engagements. So rather than relying on loaded terms like Discovery and assuming that everyone shares a common understanding of what they mean, explain to your clients, your stakeholders, and everyone involved in a project what your process actually is. Or come up with a new term for it. Just like the word “Discovery” the term “Design” can mean different things to different people, and as I discussed earlier, the lines between the two are becoming increasingly blurred. Explaining your actual process rather than relying on loaded, ambiguous terminology also gives you room to iterate on your process without having to redefine anything. Establishing a common terminology is really about not making assumptions, and being as real as possible with what working with you is going to look like, which leads me to my next point:

2. Set honest expectations

When it comes to designing products, I’m a big believer that the journey is as important as the destination. Can’t have one without the other. So if we’re being hired for our design work, we’re also being hired for the way we approach it. They are one in the same. We’re not that firm that goes into a hole only to pop out a couple months later from behind a red curtain, revealing the perfect solution. For us good design is rooted in collaboration and iteration. And to do this, stakeholders, across multiple functions and levels, have to be willing to participate. Set expectations early, making sure everyone knows what will be expected of them, and more importantly why it will be invaluable to the success of project. People have busy schedules and the last thing they want to do is sit in a couple of 2-3 hour workshop. I don’t blame them. So instead of simply stating that you’ll “need their time and commitment”, explain the outcomes that will come as a result of it. Demonstrate how early involvement contributes towards what they ultimately want and why they’re hiring you in the first place–get great product to market quickly, stay on budget, generate results, and make them look good in front of their peers and management. Last thing you want to do is find out a day before an important off-site that two key people are unable to attend because of other commitments.

3. Co-create immediately

Co-creation has played a central role in our design process for many years. Involving stakeholders early in the process has proven it’s value time and time again. Today co-creation serves as a core foundation to our engagement model with ideation workshops happening almost immediately out of the gates, even a day or two after kicking off an initiative. Including representatives from all areas of a client’s business not only amounts to more ideas in less time, but those ideas are more significantly developed through productive group dialogue and debate. And most importantly, alignment happens organically and on the fly. Compare that to the old way where we’d independently generate and fine-tune our insights, get internal alignment across project team, and only then would we share with stakeholders, only to go back into the feedback iteration cycle. Including stakeholders in up front workshops and ideation sessions can save many weeks of time and churn, not to mention the stress that typically comes with presenting new material and seeking approvals. There are also the emotional rewards that come about anytime a bunch of people, each various personalities and experiences, come together around a common goal. It’s the perfect opportunity to get to know each other as individuals, which makes for a much more meaningful, and enjoyable, working relationship.

4. Remember that being human-centric starts and ends with humans

We all place the utmost value on the experience of the end-user. All of these new processes and methodologies are lovely, but they don’t mean diddly squat without a cohesive team behind them. The experience of the humans that make up the core product team are as crucial as the group of humans that will experience the final product.

And it all starts in the first several weeks of an engagement. The tone is set. Relationships are made. How is the team working together? Are they executing against project milestones? Are they spending time problem solving as a team? Minor adjustments to the team dynamic early can be the difference between simply delivering a new product and rethinking an entire experience.

A high performing team isn’t just comprised of positions and disciplines. The best ones are made up of various soft skills and strengths that complement each other. Mix it up nice and good and adjust your approach to make sure the needs of everyone on your team are being met, and that their talents are being fully utilized. Also remember that user research is not just for your friendly neighborhood researcher any more. Everyone participates. By getting the entire team involved in user research, you ensure that the design is grounded in the user needs rather than in an individual designer’s or client’s preferences. A human-centric product starts with a human-centric team of people who care about the humans who will use their design and one another.

5. Keep your eye on prize

All of your initial activities should work towards identifying a problem and validating a solution for it. It’s easy to fall back to our old ways, especially when the project is in motion. So plan ahead and establish a framework to help you stay focused on the problem.

Write these two questions on the back of your hand. as you jump into the early phases

- What are we working towards?

- Will this activity or artifact make a direct and necessary contribution to that said outcome? And, if the answer is yes, then…

- Are you 100% sure about that? Might there be an even easier way to achieve a similar outcome? (if unsure, ask a pal for help.)

If you feel like you might be doing too much, you most definitely are. Trust your gut. Do it for the people.

The most important thing to remember is that Discovery is always a Discovery in and of itself, one that you will never be done discovering.