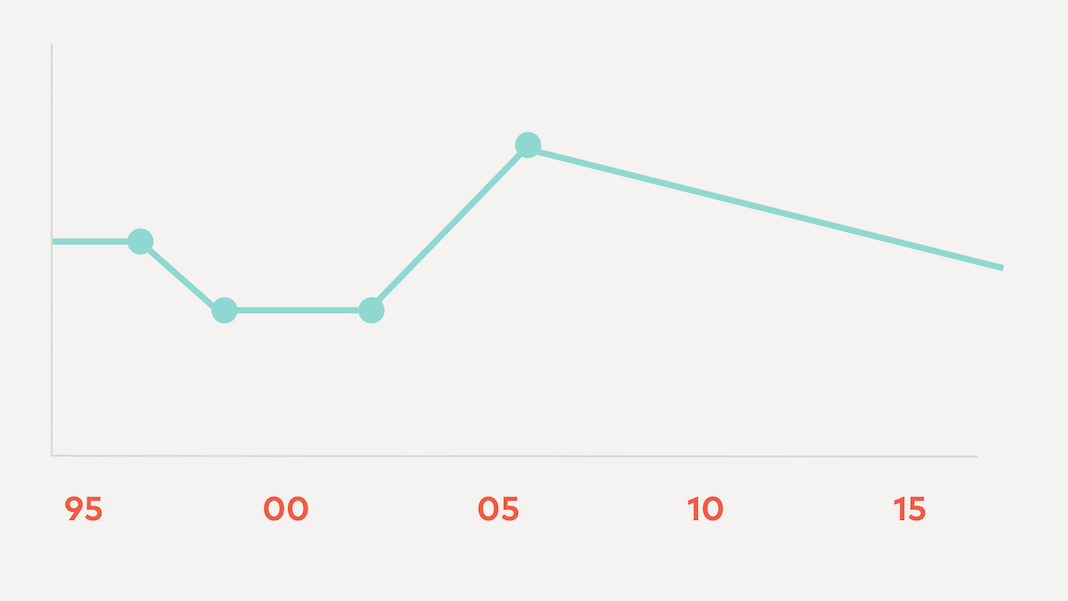

Is the hype around the gig economy all a sham? It’s a fair question, and one a lot of people are asking since the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) published their survey findings on Contingent and Alternative Employment Arrangements earlier this month. It’s the first BLS survey of its kind in more than a decade (the last survey was conducted in 2005) and its findings, which concluded that only about 10% of the U.S Labor force have “alternative work arrangements” for their main source work, come as a bit of a shock. They stand in stark contrast to other recent reports, which have estimated that the gig economy comprises (or will by 2020) close to 40% of the U.S. Labor Force.

But can the numbers lie? Maybe not, but they don’t necessarily tell the whole story. While other recent reports may have overestimated the size and the impact of the gig economy on the labor force, there are good reasons to dig deeper into the BLS data and to continue conducting research that can help paint a more complete picture of how the U.S Labor Force is changing.

Here are a few of the ways in which the BLS report fails to tell a complete story:

- It does not represent workers who participate in gig or independent work in addition to their full time jobs. According to a McKinsey report published in 2016, those doing gig work to supplement their incomes comprised 56% of the total group surveyed. This group is completely unaccounted for in the BLS data. The survey also indicated than in order to be included in the data, a person must have done some kind of gig or freelance work within the last week.

- It does not provide (nor does it attempt to) a definition of the gig economy or of what a gig economy worker actually is. Generally, there is a little consensus on what the gig economy is. Some include independent contractors, musicians, and DJs alongside app-based workers who do things like drive for Uber, while others focus solely on this later group. Without a clear definition coming from anywhere, it is difficult to use the BLS data set to make any kind of claim about the actual size, prevalence, or impact of the gig economy on the shape of the U.S. Labor Force. In our recent white paper on the gig economy, we defined the gig economy as comprised of any worker who engages in work via short-term contracts, freelance work or one-time gigs, both to supplement their income or as their main source of income, and through platforms like Uber, Upwork, and TaskRabbit or more traditional channels. We also included both independent contractors and those who participate in the share economy to earn income (ie. rent their apartments on AirBnB). While this is the definition we used in our research, it is by no means a standardized definition that is agreed upon by everyone, but it suggests the breadth with which the term can be applied.

- It does not account for subcontractors, or, workers who are employed through a third-party vendor that is contracted with by an employer (think a bus driver hired not by a school district, but by a transportation service). As subcontractors, these workers are less likely to receive the same kind of benefits and pay that a direct employee of a company or organization might and often have less job stability, fewer workers rights and less room for career growth and advancement–not at all unlike the problems faced by gig economy workers. To boot, subcontracting is prevalent in industries where job growth has been most robust since the recession–ie. personal and home care, food service and preparation, and janitorial or cleaning work.

- Relatedly, because of the changing nature of employment, workers who participated in the BLS survey may have miscategorized themselves. As economist Katherine Abraham recently pointed out in a New York Times article “there was evidence that workers struggled to accurately report and classify work that did not fall neatly into traditional buckets. Some Uber drivers, for example, might consider themselves employees of the ride-sharing company, even though legally classified as independent contractors. Some Amazon warehouse workers might report being employees of the e-commerce giant, even if employed by an outside staffing firm.”

- Finally, the methodology used to conduct the survey may simply be outdated, and not structured in a way to accurately reflect how the U.S. Labor force operates. For example many people earn their incomes in ways that they may not consider to be “employment,” ie. renting out their homes on AirBnB. The survey questions provided no means of accounting for workers who derive income through sources that cannot be clearly defined as “employment.”

So is the hype around how the gig economy is shaping the workforce a sham?

It’s possible. But there is a reason this narrative resonates: something about the U.S Labor Force and the way in which individuals relate to employers and to work itself is in fact changing.

A recent Deloitte Survey of 10,000 college educated millennials working full time found that millennial opinions and perceptions of businesses are declining, and that flexibility in their jobs–the kind enabled by the gig economy–is a top priority for millennials and a key to employee retention. These same workers don’t feel like their companies are doing enough to prepare them for the future, leading to less confidence in their future employability and in their employers. These workers want their employers to invest in their futures, in the same way that they have invested in themselves via their expensive educations. And while these trends may be reflective of the attitudes of a very specific demographic, they help paint a more complete picture of a labor force that mistrusts employers and feels emotionally disconnected from the values and missions they hold. And as practices like contracting, subcontracting, and tech enabled gig work widen this rift (a rift already being felt by the most educated and fully employed workers) between employee and employer and undermine trust, these perceptions will likely continue to deepen.

Within this widening chasm, there exist opportunities for businesses (as employers) who can rekindle a connection with their employees by offering better benefits, more flexibility, continuing education and stronger company cultures. Furthermore, there exist opportunities for businesses selling to these workers, who can design services and products to help fill in the gap left by employers–namely in the realm of direct-to-consumer benefits, insurance policies, and financial tools to provide workers access to the kind of security and stability that once belonged to full-time employment and has become increasingly hard to come by–both for workers in the gig economy and in more traditional jobs.